Researchers from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Harvard University have uncovered a fascinating truth about how people share money. The way communities are socially organized may quietly determine who benefits the most from cash assistance programs, even when governments assume equal impact across households.

The Secret Life Of Cash Transfers: Family Bonds Versus Age Alliances

Background

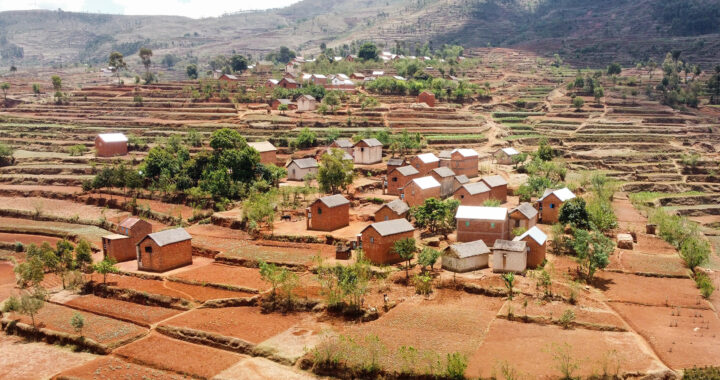

In some East African societies, life revolves around extended families. Family members routinely share across generations to support one another regardless of age. In other regions, people strongly identify with age groups rather than family lines, turning peer networks into powerful support systems while unintentionally sidelining younger or older dependents.

The researchers studied two government programs to observe how money travels through these different social systems. These were the Hunger Safety Net Program in Kenya, which provides cash to vulnerable households, and the Senior Citizen Grant in Uganda, which delivers monthly payments to the elderly equal to one-fifth of individual spending.

Key Finding

•Family Bonds Drive Redistribution: In family-oriented communities, money flowed naturally between grandparents, parents, and children, reinforcing strong intergenerational safety nets that stretched beyond the original recipient.

•Child Nutrition Gains in Kin Systems: Just one extra year of pension access in Uganda reduced child malnutrition by nearly 5.5 percent in kin-based regions, proving that funds intended for seniors often nourished the youngest family members.

• Risk Depends on Social Structure: Age-based communities created risks for children and elderly individuals, who lacked access to peer networks. Kin-structured regions showed risk concentrated within entire families rather than specific age brackets.

Takeaways

Policymakers designing financial support programs must recognize that direct recipients are not always the final destination of redistributed money. Cultural pathways silently redirect resources according to social norms. Financial aid may appear effective on paper while accomplishing little in practice without accounting for those hidden flows.

Intergenerational poverty reduction strategies should therefore be tailored with precision. In regions where families share across age lines, sending funds to older adults can unintentionally strengthen child welfare. However, in age-oriented societies, that same strategy may stall entirely, leaving dependent generations without meaningful benefits.

Development agencies may also reconsider how success is measured. Instead of tracking only individual recipients, evaluations should observe secondary and tertiary beneficiaries. Knowing where and how money travels after distribution is as important as the initial placement. Social architecture, not budget size, may determine long-term impact.

FURTHER READING AND REFERENCE

- Moscona, J. and Seck, A. A. 2024. “Age Set versus Kin: Culture and Financial Ties in East Africa.” American Economic Review. 114(9): 2748-2791. DOI: 1257/aer.20211856